By Caitlin Cacciatore, Felicity Howlett, and Raquel Neris

Project Narrative

In March 2020, the world as we know it experienced a massive upheaval. The first case of COVID-19 in New York State was recorded on March 1st, 2020. A series of events followed, including Governor Andrew Cuomo declaring a state of emergency on March 6th, NYC guidance to avoid crowded public transit the following day, the March 12th closure of Broadway, and the declaration of a national state of emergency, as well as the World Health Organization’s announcement of a global pandemic on March 11th, 2020.

For many, life moved online. Non-essential jobs and nearly all events went virtual. Public schools, colleges, and universities closed their physical doors and transitioned to online learning. Zoom emerged early on as a serious contender for allowing us to continue meeting in groups in a synchronous manner. We were all isolated and lonely despite these virtual interventions, but even in the face of these challenges, we adapted and began to adjust to what became our “new normal.” Unfortunately, many elders were left without Internet connections, Internet-connected devices, and the digital literacy needed to operate such devices.

Digital Humanities (DH) has often overlooked the elderly community, perhaps in part because of the perceived and actual lack of digital literacy amongst seniors. However, the DH community is remiss to overlook our elders. Digital Humanities is fundamentally about humanizing, decolonizing, equalizing, and removing barriers to access in the digital world. The digital humanities field has committed itself to equality and equity in the technological sphere, yet a major demographic has been largely forgotten about. According to recent Census data, people over 65 constitute 16.5 percent of the population in the United States. If we extrapolate from population counts, this amounts to almost fifty-five million individuals from all walks of life.

The significance of bringing the elderly community into the technological fold cannot be understated. Despite an ongoing global health emergency, many people continue to live full, vibrant lives well into their ninth and tenth decades, and beyond. In a very visceral way, they and others of their generation built the world we are currently inhabiting. “According to US Department of Veterans Affairs statistics, 240,329 of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II” were still alive in the year 2021. (National WWII Museum)

Isolation and loneliness are rampant amongst elders. Lockdowns combined with a fear of contracting COVID drove many seniors into their homes, with little outside interaction. Additionally, ten percent of the US population age 65 and older are homebound, or in need of home-based care, and cannot go out due to disabilities, illnesses, or other maladies. By providing a synchronous, virtual online music experience, we hoped to reach just a few of the millions of homebound seniors in the US. We wished to take a step in the direction of bringing homebound and isolated seniors into the purview of the Digital Humanities.

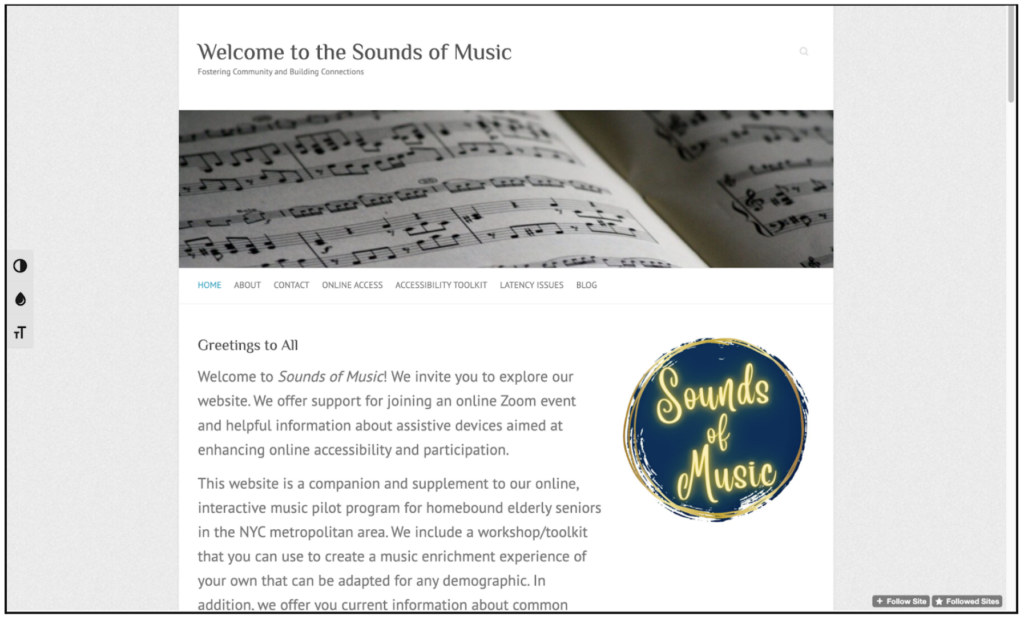

We envisioned the Sounds of Music as a step towards including an overlooked population in DH. Sounds of Music is far more than just an interactive online event; it’s a cultural experience, as well as a chance to socialize with others and share memories, thoughts, and songs. We built a website that hosts an Accessibility Toolkit, a guide to Internet connectivity and setting up and using Zoom, as well as a blog that describes our thought processes, provides suggested reading and online music programs similar to ours, and lays out our manifesto.

Sounds of Music has always been very much about people. People – from their wants and needs to their desires and limitations – have informed every part of our user-centric design, from our website to our pilot programs to our Accessibility Toolkits. We have defined the Sounds of Music by our target users amongst the elderly population and designed with the extreme user in mind. We envision a hypothetical individual with any combination of auditory, visual, or physical impairments and/or disabilities – an elder who might have a computer and an Internet connection, but who feels uncomfortable and out of place in the digital world. This individual’s feelings are compounded by disability, and frustration at not being able to navigate websites in the same manner as a non-disabled person might, due to barriers to access.

We are committed to making the Sounds of Music accessible to all who might wish to partake in our music enrichment program. We were driven by the belief that music should be for everyone and anyone who wishes to listen, and we wish for our communal experience to be an uplifting, joyous one. We believe in creating a safe, inclusive space for those who enjoy music to discuss memories that arise, connections that present themselves, and other elements of the musical experience.

We wish for our audience to come away from the pilot program smiling and feeling connected and engaged. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, elderly individuals have not experienced the type of connections that they once enjoyed freely and without concern for their health. We seek to remedy this by providing an online, virtual environment that is both a safe space for sharing music and memories, as well as a community-building experience during which new friendships can be formed and maintained.

Ultimately, our vision is to build a bridge between the DH community and a hitherto understudied demographic – a demographic that we have found very receptive to technology, eager to learn, and quick to pick up on skills needed to navigate the online world.

Audience

The inspiration for our project comes from Concetta Tomaino’s music therapy program, “Music for Veterans,” at the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function (IMNF). Executive director of IMNF, a certified music therapist, and former president of the American Association for Music Therapy, Tomaino is a scientist, humanist, and educator by inclination, and she has conducted extensive research on the interrelationships between music, neurology, and rehabilitation. Oliver Sacks, with whom she worked for many years, dedicated his book, Musicophilia, to her. She has presented lectures to a variety of national and international institutes and associations, and she teaches introductory courses in music therapy and “Music and the Brain” at Lehman College, CUNY.

Our team member, Felicity Howlett, volunteered as a piano player for the weekly veterans’ program at the IMNF residence in Wartburg, an adult care community in the Bronx. Participants included people who attended the Wartburg daycare programs and who suffered from various afflictions of the elderly, including early traces of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, physical handicaps, fragility, depression, and memory loss. Week after week, she witnessed how music participation created dynamic connections for people, how listening and talking about music inspired memories and discussion, and how music could transport individuals from an antisocial stance to a willingness to accommodate, to take a turn at the mike, tell a story, play an accompaniment with a simple instrument, sing along with the group, or even demonstrate dance steps.

When the COVID-19 pandemic closed down the in-person program, “Music for Veterans” moved online and assumed a new shape. It was no longer possible to distribute drums, rattles, or other simple instruments for ensemble activities, and latency issues inhibited group singing and playing together. New possibilities included watching and discussing music videos together, singing along with a karaoke text provided on our screens, listening to individual solo performances or two or more people attempting to perform together, as well as the usual discussions inspired by the music. It became apparent that commitment to a weekly meeting, stepping out of isolation and into a welcoming group, and meeting familiar faces, no matter how virtual, were powerful and restorative elements of the experience. The new arrangement created interest among people who were unable to attend weekly sessions in the Bronx, but we lost contact with several elderly people who did not have online access.

When Howlett entered CUNY GC as a MALS student in the fall of 2020, academic participation was virtual. At least for business and education, tremendous efforts were underway to enable life to proceed as usual, but virtually, and often from private residences. As so much of the population was working from home, connectivity issues gained greater attention. This intense push for fluidity and interactivity had particular advantages for a population that had been relatively stranded, overlooked, and untapped—a population that, for one reason or another, could not leave home.

Our team focus is on a population that can enjoy a vacation from isolation by virtually participating with other people over the internet. While our program may prove to be therapeutically beneficial to its participants, we are simply providing a platform for people to enjoy sharing musical interests with one another through an interactive, online program. Our project evolved as we explored how to create a structure for this purpose. While we do not mean to focus exclusively on the elderly, older people represent a significant segment of the population that tends to become more isolated with the passage of time, whether because of age, fragility, or various disabilities that accompany the aging process. Our interest is to combine the joy of music with an invitation for people to enjoy a social, participatory, recurring online event.

Through participation in such a virtual program, individuals may reconnect with parts of life they may have lost, or at least had to forego, due to their isolation. Doors may open for some people who have never had the opportunity to enjoy in-person community activities. For people who may feel that age or fragility is robbing them of their autonomy, the program presents an opportunity to appear among other people in real-time, to be recognized, and to share. Music serves as a revitalizing element in this arrangement, as impetus, substance, and a potential direction for exploration. It may also, simply, offer the opportunity to share in the joy of music.

Weekly participation in a social setting may encourage people to get to know other participants, foster interest, and concern for others, if, for example, someone misses a session. Friendships may blossom among people who discover shared interests, and as online activities become familiar, deeper individual explorations of the internet may lead people to other resources. The potential benefits of encouraging virtual participation for interested, homebound individuals over the internet are hampered only by what assistive devices are necessary to enable an individual to fully enjoy online interactive access. Our accessibility toolkit offers assistance for these issues, particularly for hearing problems, visual impairment, and physical handicaps. We also describe a selection of voice-empowered devices. Some potential participants will need to have assistive equipment installed or custom-tuned, and that may require individual attention, at least at the outset. As the benefits of internet participation for this population become more apparent, and greater attention is being paid to these issues, we hope that the segment that is most isolated will enjoy greater online access, share in the joy of music, and the pleasures of getting to know one another through virtual participation.

Project Activities

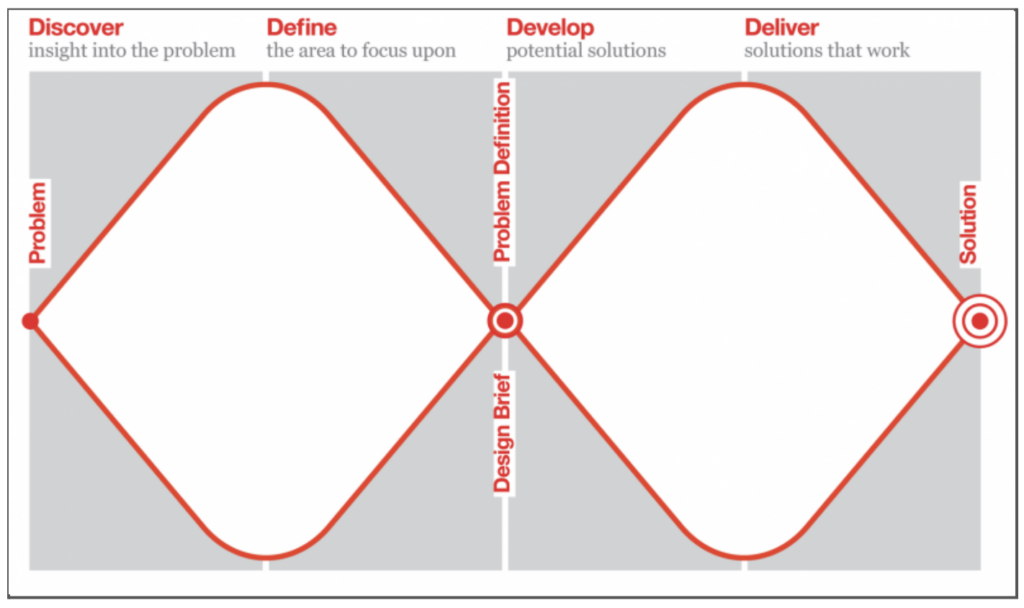

At the beginning of our project, we had many ideas about how an interactive online experiential music program could be and what tools we could use to develop it. However, we were also aware that we had a biased vision. That could only be corrected by following a design thinking framework based on the premise of testing, learning, and iterating our ideas before officially launching it. Therefore, we followed these steps:

Step 1: Discover

We explored ways to better understand our audience’s needs and expectations, learned about assistive technologies and how they could enable handicapped individuals to attend our program, and researched other online music programs so that we could be inspired by them and understand how we could be different.

Step 2: Define

We generated different ideas for the program, and based on one format, we designed our prototype, which we called the “Pre-pilot Program”.

Step 3: Develop

We tested our prototype with an audience to receive feedback and understand what works (and what doesn’t work) for our program.

Step 4: Deliver

Based on our learnings, we iterated our program and created a second experience called our “Pilot Program”.

We represent those steps visually as a Double-Diamond framework in the image below:

The Double Diamond (adapted from British Design Council)

Work schedule and deliverables

The four-step framework that guided our project development involved a four-month effort focused on achieving these deliverables:

1) Sounds of Music Website

We developed a public-facing website using CUNY Academic Commons, powered by WordPress, presenting the Sounds of Music program with information about online access, assistive technologies, and latency issues, which are problems of real-time, synchronous communication in online meetings. We also presented a blog with relevant information about using music to engage in social interactions, suggested reading about music for a non-specialized audience, and our manifesto.

The website itself also presents special features regarding web accessibility, such as the options to change contrast and font size.

We established our website as our primary communication channel with the audience. However, we also plan on creating a Facebook page for the project, where we will disseminate updates about our program. The launch of our Facebook page should happen together with the program’s official launch. It will serve as a platform for building our audience, creating new content related to the Sounds of Music, and making public announcements.

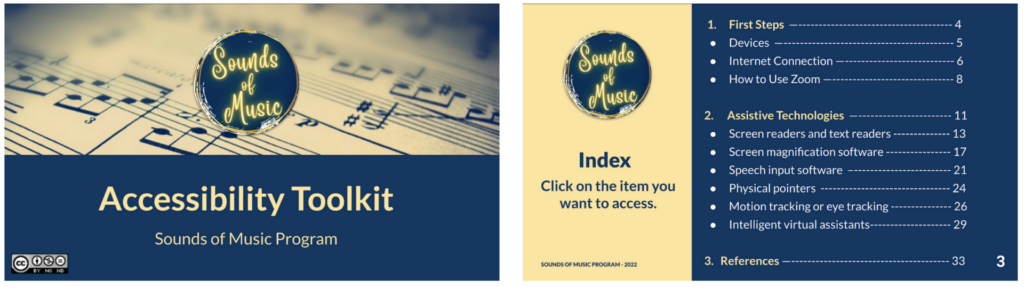

2) Accessibility Toolkit

Our Accessibility toolkit was developed by collecting data from consulting experts in the field of Disability Studies and aggregating our research to find relevant information about assistive technologies and accessibility resources. Divided into two sections (First Steps and Assistive Technologies), it is offered to the audience as a downloadable PDF with important information for people with different disabilities to access our program. This document presents details about internet connection, how to use Zoom, and an overview of several assistive technologies. We offer a list of tools, including screen readers and text readers, screen magnification software, speech input software, physical pointers, motion tracking, and intelligent virtual assistants.

Sounds of Music Accessibility Toolkit

In addition to that, we also plan to provide a CSV file with information about each assistive tool. Both documents should be constantly updated so that our data doesn’t become obsolete.

3) Sounds of Music Workshop

Our Sounds of Music workshop is a predefined format for an online musical experience, with guidelines for conducting activities with the audience. In short, we apply these elements:

- Meetings with a 90 minutes duration;

- Zoom as our online meeting tool, chosen for its wide adoption;

- Group size ranging from 3 to 8 maximum, establishing a comfortable environment for everyone to participate;

- A facilitator for the experience, provided by our team.

During the programs, we promote several activities, such as watching music videos, sharing listening selections and favorite performers, singing-along using lyrics provided on the screen, and participating in discussions of thoughts and memories inspired by the shared songs.

For the pilot sessions, we outreached participants using both email and telephone. We sent reminders through email before the workshops and after each meeting, we also thanked each participant and requested their feedback.

4) Sounds of Music Workshop Toolkit

Sounds of Music Workshop Toolkit is a do-it-yourself guide created to assist anyone interested in replicating the Sounds of Music program and shaping it for a specific set of participants. As this is our last deliverable, it is still under development and should be launched by June.

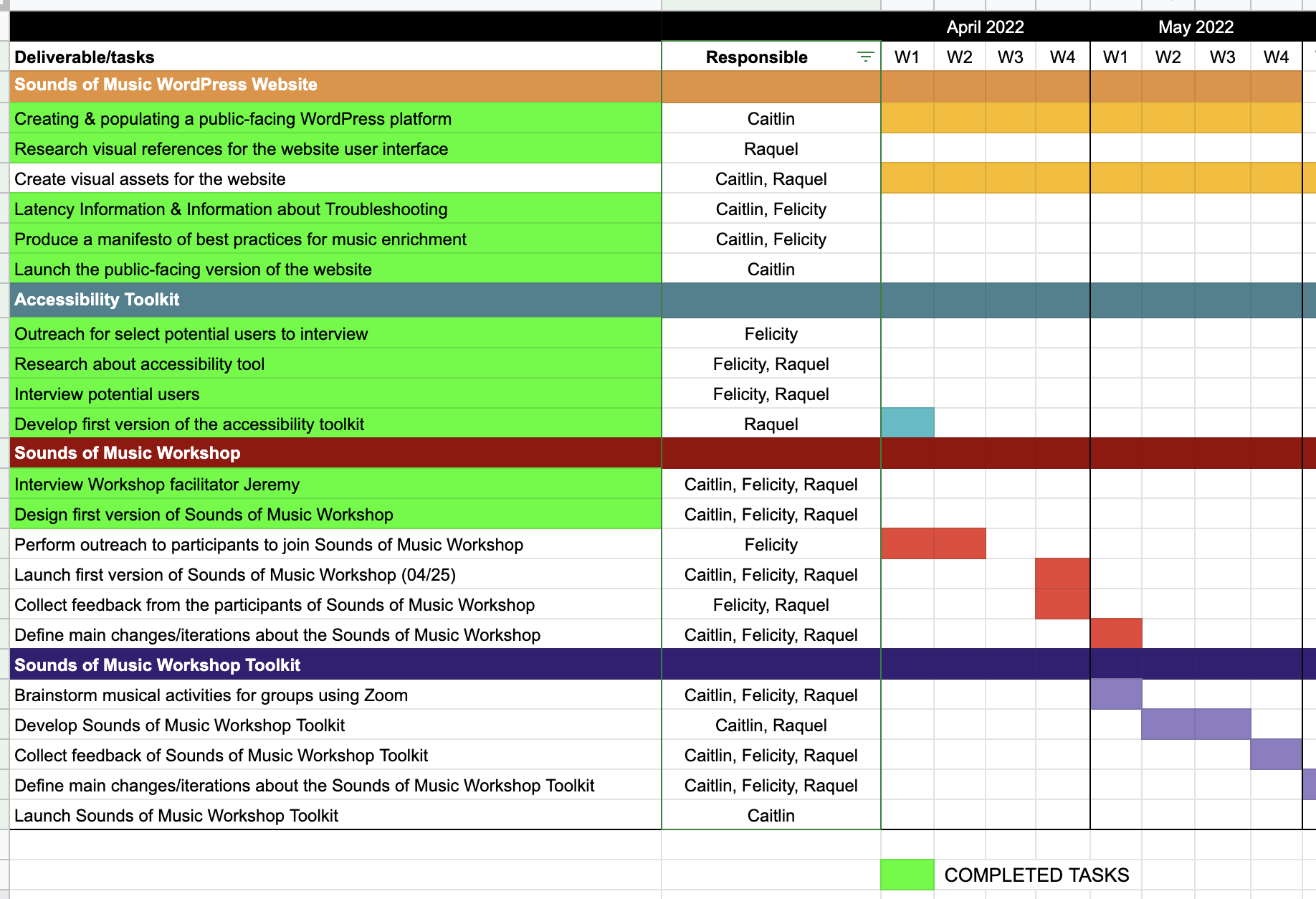

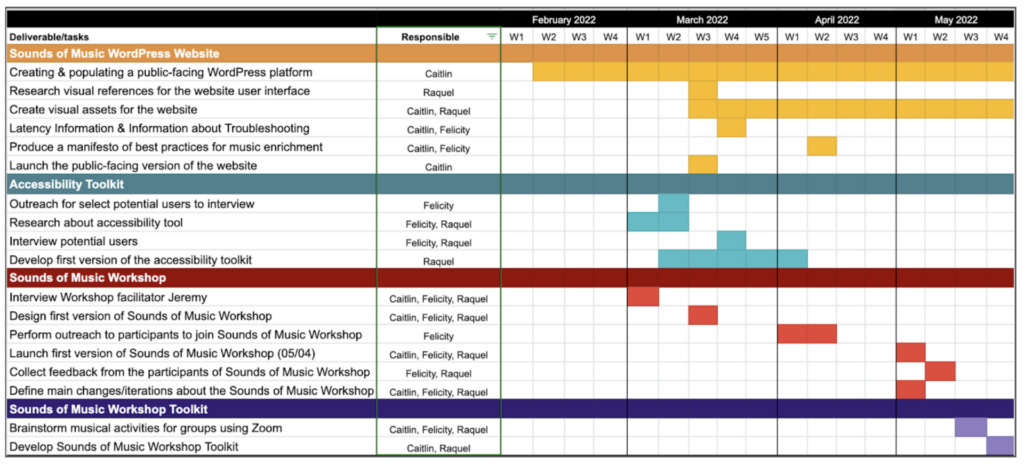

The deliverables were developed according to the schedule below:

As illustrated by the Gantt chart, our project management followed an agile methodology. We broke the project into several phases in which we constantly involved the collaboration of other stakeholders, searching for continuous improvement at every stage. We used Trello, Slack, and Google Drive as our main tools for project management, which allowed us to have a solid base of communication from beginning to end. We also had weekly meetings every Monday and Wednesday, which enabled us to maintain the momentum of the project.

Evaluation

Our primary feedback came from the Sounds of Music pre-pilot and pilot sessions. During the pre-pilot session, we rolled out our website in front of a live, synchronous, virtual audience joining us from the comfort of their homes. Additionally, we provided a music enrichment experience lasting about an hour. We had approximately eight audience members, ranging in age from 75 to 92. Our audience proceeded to critique our website, asked us questions about our premise, and offered feedback about various aspects of the musical enrichment program. Their feedback was invaluable in making our ninety-minute pilot session a success.

Some members of our audience suggested that our program lacked spontaneity, while others felt that we needed more structure and better continuity between songs. We learned from our pre-pilot program that we needed to achieve a more profound understanding of our target audience. Ultimately, this resulted in the complete restructuring of our pilot experience. We sought out and found a facilitator and mentor in Jeremy Deliotte, who typically works with veterans in the capacity of providing music therapy and enrichment.

With Jeremy’s assistance and our audience’s feedback, we decided to ensure that anyone could request any song, at any time. During our pilot session, a slightly smaller group gathered. After we all introduced ourselves, Jeremy proceeded to ask each participant a variation of the questions, “What music has been on your mind? What songs have you been thinking about lately? Have you heard anything recently that has moved you?” These questions and queries like them yielded fruitful answers, with each participant taking time to give it a moment’s thought before some song or another would come to mind, at which point we would source the song via YouTube and share it through Zoom.

The pilot program was a fantastic success. Gennie Green said to us, “Music has so much power,” when she was describing the emotions evoked by the songs we had listened to together. She added later, “Everything has a rhythm to it,” citing our heartbeat as a fundamental example of the rhythm that connects us to one another. One of the songs we listened to was Tony Bennet’s “Once Upon a Time,” which was the first song Madeline Lovallo had danced to with her husband at her wedding, more than fifty years prior. Later, in a private call to Caitlin, she confessed that she “was transported back to the day of her wedding,” when she heard the song. The transformative, transportive power of music is simply remarkable, despite the fact that listening to music has largely become a solitary endeavor, both with the advent of headphones and the onset of COVID-19-related restrictions on gathering and the unique and pressing danger posed to the elderly.

We sought to change this solitary activity into one that was shared, as music has been through most of human history. Music was intended to be shared, and our pilot program was a vibrant example of how and why music should be shared. Every participant reported hearing a song they hadn’t heard before – music from an era or location that had previously passed under their radar.

We learned through user feedback that the most single fundamental part of any experiential music enrichment program such as our own is agency – the freedom of the participants to choose which songs to listen to next, and the ability to have a voice in order to request songs that moved them on a personal, emotional, or spiritual level. We learned from our pre-pilot that assuming which songs participants might wish to listen to, and coming prepared with a playlist, was in error. Though some structure is needed, and can be provided by a skilled facilitator such as Jeremy, most of the program’s time should be spent in organic conversation and honoring spontaneous requests for songs.

The pilot program was a success because we loosened our structure and gave our participants more agency, freedom, and power of choice. The musical experience is one of the most dynamic aspects of the Sounds of Music program. It can be easily reproduced with any small group.

We also received feedback from our colleagues during the dress rehearsal for the Showcase, which we incorporated into our presentation. The presentation, like the website, went through many iterations, small tweaks, edits, and revisions until they were perfected. It is also noteworthy that our website received a total of 395 views from 36 unique visitors, indicating that the majority of our visitors browsed around through several pages on our website.

The website evolved rather organically. Though we did not solicit feedback on our website outside of the pre-pilot session, it went through dozens of versions, each with the goal of making the website more comprehensive, more aesthetically pleasing, and above all, more accessible. Early on, we installed an accessibility toolbar, which toggles various combinations of high-contrast, grayscale, and large-text modes. The website also hosts a version of our Accessibility Toolkit, which is designed as a portable, adaptable, dynamic resource for accessibility tools that help mitigate barriers to access presented by physical, visual, and/or auditory disabilities.

Looking back, we might have solicited feedback from individuals well-versed in web design. We could have also reached out to individuals in the disabled community for the purpose of tweaking and expanding upon the Accessibility Toolkit.

Continuation/Future of the Project/Sustainability

Our project is now independent. While we may continue to tweak it, we achieved our goals. Our website provides a project description, information about internet access and Zoom sessions, opportunities to explore assistive devices, latency issues, readings about the role of music in human life, and more. It frames an online, interactive music program for people who are isolated from opportunities for social interaction. Our concept is available to anyone who is inspired to implement it, and it has the flexibility to accommodate specific situations and interests. For example, a program designed to connect isolated members to their church community might be built around sharing favorite hymns. Elderly immigrants from a specific geographic area might experience the awakening of memories from sharing songs that were once part of their lives. After visiting our website, a family member might be inclined to organize an interactive musical reunion for elderly siblings and intimate friends. Revisiting once familiar music online together may rekindle long-forgotten memories and inspire reflection, laughter, and even a sing-along. While the effects of such online participation may prove to be therapeutically beneficial, our basic goal is simply to provide an opportunity for social, recreational, and musical connections.

We offer links to other, more formally structured online music programs, but we have chosen to keep ours flexible. For our “pilot,” we restructured our program plan and included an experienced music program “facilitator” to be our host. Despite its success, we have not stipulated that choice for everyone nor have we suggested that interested parties follow a set program protocol. We leave these considerations open to be worked out depending on the individual program. Although the musical options for our recent pilot seemed almost limitless, they were guided by a professional who ensured that the underlying dynamic did not flag, and that everyone who attended was acknowledged and felt welcome to contribute and participate.

Our future music program has an outstanding problem: Will it continue, and how will it be mentored? We have presented the program concept for people to study and implement as they see fit. Yet, we discovered that our program is more successful with an experienced guide who makes sure the meeting is inclusive and everyone has an opportunity to participate. This area requires additional discussion and thought: inclusivity and participation are at the heart of our efforts. Jeremy Deliotte, our mentor, and the host of our second program, is impressed by the program’s dynamics. He thinks it might catch on very rapidly. Yet he also believes that when Sounds of Music offers a program, it needs a shepherd, a facilitator. How can we take responsibility for making such a program possible? And how can we not make it possible when it has such potential?

Several avenues are open for further exploration, including:

1) If Jeremy were interested in hosting such a program, or training additional hosts, we could seek funding for its continuation while it is attached to the GC Academic Commons. We would only need to finance the time and expenses for an experienced practitioner to guide the operation of the interactive music program. Such a concept might provide opportunities for student volunteers and interns as well. One of us (or a student in Digital Humanities) could maintain the website and the toolkit.

2) The Digital Humanities program already has an area devoted to Storytelling. Our program encourages spontaneous musical storytelling that might be understood as an incredibly rich, and perhaps untapped, source for storytelling archives development. How these areas might find compatibility and resonance is worth exploring.

3) We have initiated searches for possible links with existing programs and institutions, but we looked into this area mainly for its future potential. We may discover valuable connections as we probe more deeply. For example, Dorot, a social services organization on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, offers a large collection of free, online programs and activities, many of which are aimed at the elderly. We might make connections with their music programs as well as to their legacy explorations (adding a musical component, enabling web searching). Several rehabilitation centers expressed interest in our program but could not guarantee the reliability of the Wifi connectivity for their clients. One new residential rehab with top-of-the-line internet connectivity invited us to return in a few months. While its equipment was excellent, solutions for scheduling individuals for Zoom sessions and the concomitant details involved in enabling individuals to participate were still being worked out.

4) What types of outreach can we develop to locate and connect individuals who are isolated? And how can we help establish reliable online connectivity for them? From word-of-mouth connections made by family members and caregivers to suggestions from community programs, and potential media links, this area is wide-open for exploration. Certain areas of our project, such as the assistive technology toolkit, can be of immediate assistance: the portable toolkit can be copied, shared, and utilized. It is more difficult to package the concepts behind the interactive program. How do we balance the sensitivity and consideration that must be involved in gathering people who have been isolated and may have little or no experience in virtual interactivity with our interest in sharing the potential benefits of our program with them?

5) Lack of internet access and the unreliability of internet connections are among the greatest drawbacks of our present program. Given the continuous acceleration of online connectivity, there is good reason to believe that connection and accessibility will continue to improve and more and more people will gain access to the internet. For assistance in this area, we might explore service organizations, charitable foundations, and insurance companies. If music and social interaction promote health and welfare, certain companies may find it financially beneficial to contribute to the promotion of such issues.

We are not prepared to launch our program into the wide open waves of social media, nor are we convinced that it should be presented as a free-floating entity. We are prepared to create links to areas that already have an invested interest and sensitivity to helping individuals gain access to the internet and overcome some of the difficulties of limited mobility and isolation by sharing music, memories, and new interests via online participation.

With each day, how music and human life interact and what this relationship means receives additional recognition, investigation, exploration, and celebration. Our project attempts to open doors to these physical, emotional, and intellectual benefits as people celebrate life through sharing music.