The Mainframe Project White Paper

Project Narrative

Digital humanities as a discernible field of inquiry grew up with the increased prevalence of personal computers. As a consequence of the discipline’s emergence within this historical period, little intellectual output in the field interrogates pre-personal computing subjects. Mainframe computing in particular is bereft of attention in the humanities, despite the fundamental contours grooved and legacy inherited from these machines, their operating systems and software in contemporary computing life. This project aims to build a web site collection of ‘thickly’ described informational resources about mainframe computing, delivering the prerequisites for further research about mainframe computers in the digital humanities. The operating systems and software used on mainframes began the trend toward abstracting the user from knowledge of how hardware processes data, yielding a world where nonspecialists during computers in everyday life. The objective in collecting archival material will be to grant a sense of the world in which mainframe users interacted with computers. By gathering marketing and instructional material about mainframe computing, this project provides a resource for DH scholars and interested students in the cultural context surrounding computers in the post-WWII era up to the emergence of the personal computer.

The Mainframe Project is a digital collection of archival images ranging from advertisements to marketing brochures to instructional material. By focusing on the computing devices in the workplace before the advent of personal computers, we hope to defamiliarize some of common assumptions about computing informed by contemporary culture. The archive creates a starting place to think through how the social context around computing from 1950 through the 1970s is different from and informs our view on computers’ place in our cultural imagination. Specifically, this project probes the underlying influence of war on the rise of computers, and also the gender politics of operating these machines in the business place before the personalization of computing. It will conduct these types of investigations by looking at archived material such as advertising, manuals, and other marketing ephemera.

Environmental Scan

When looking on the internet for archives, collections of material or scholarship on mainframes, the results baffle naive expectations. The public institutions interested in computing assume an in-person experience as the background to understanding the material. At the least accessible end of the spectrum, the Computer History Museum, both in current form and its archived version, focuses on driving traffic of an enthusiast nature and a eye towards projecting history into a future utopian visions typical of Silicon Valley. The Centre for Computing History provides a retro themed archive of ephemera, though most of that is geared towards experiences rooted in personal computing and gaming. The archival material posted on this Cambridge-based museum is well organized, but each artifact is furnished with little context in which to understand the subject matter without prior knowledge. Further internet searches for academic work on mainframes is confounded by a fog of sales blog posts from contemporary mainframe manufacturers and software development consultants. Still, a few scholars will guide MPP with subject-specific study and methodology useful in a humanistic study of mainframe computing.

It would be neglectful to omit the masterful work done by Tung-Hui Hu in A Prehistory of the Cloud. The Mainframe Project finds intellectual footholds for its intuitions in this book’s work connecting computing past to present, especially the connection between time-sharing and cloud platforms. The second chapter of the book, “Time-sharing and Virtualization” analyzes the rhetoric of computer scientists, as well as “political, legal and nonspecialist documents” to identify the complicity of time-sharing in the “economic shift away from waged labor and toward…the economy of ‘immaterial labor’…of flexible labor that encompasses even seemingly personal or unpaid tasks, such as writing a review for a favorite product on Amazon.com” (Hu, 39). In this account, time-sharing on mainframes, embracing a rental model for computer resources based on processing hour, creates a “user” subject grounded in seeing their time as variously lost, stolen and potentially recoverable. In effect, the computer user is made “equivalent to his or her usage” by time-sharing, “yok[ing] the user’s labor to the labor of the computer itself…fashion[ing] an efficient worker capable of flexibly managing time” (47). Maneuvering between accessible technical explanation and the explanation of how knowledge work is bounded up in the rhetoric and economics of time-sharing, A Prehistory of the Cloud serves as a model for the type of scholarship the Mainframe Project hopes to inspire in future iterations and scholars.

In order to view the user subject in mainframe computing, and avoid simply recapitulating the technical details, the Mainframe Project considers the experience of the knowledge worker. Alan Liu’s The Laws of Cool offers any plethora of cultural exegesis about knowledge work. For instance, how an office space populated with computers tranforgrafies labor as conceptualized by Marxist theory, the aforementioned “waged labor,” into an unromantic form of alienated labor for knowledge workers. These “chimerical creatures who owned no productive property yet represented proprietors…were the class of untragic labor and undemonic godhood…merely routine submission and petty bossiness” experienced a world in which coolness of affect, exemplified by professionalism in the workplace , was spurned on by automation, i.e. the transfer of labor of a computer (Liu, 1112). Representing capital and labor, and yet having neither in the traditional sense, the knowledge worker is responsible for providing a service rather than a product, an output unmeasurable only by time expended at the workplace. As Liu puts it in the cadence of a commandment, “thou shalt not know joy or sadness at work. Neither celebration nor protest nor mourning is on the clock” (Liu, 1189). Liu also discusses the cultural perceptions, popular and literary, surrounding mainframes in the 1960s, which will help bolster our directions in research and sourcing archival material for the Mainframe Project.

The affordances of software, the way it can change the content of output as a result of changes in production, will not be ignored in the MPP collection. Matthew Kirschenbaum’s extended meditation on word processing, Track Changes, expresses the benefits of this software for professional writers. Although Kirschenbaum explicitly focused on word processing in the personal computer age, the insights into how word processors operate as tools compared to previous writing technologies are an inspiration for MPP’s inquiry into the mainframe end-user software. The stubbornness with which a small niche of authors stick with Wordstar is reevaluated as a practical decision, with writers opting for an experience that abstracts away concepts like pages, as a medium that “resembles a longhand approach to document composition, with all the freedom and flexibility that it affords: (Kirschenbaum, 4). The advantage of a word processor like Wordstar shines in the editing process: “Whereas the strike of the typewriter’s keys forces the writer ever forward, character by character, line by line, WordStar’s intricate layers of push-button inputs allowed far more freedom and flexibility.” Of course, the MPP project will need to engage with line editors rather than graphical word processes when talking about document creation in the height of the mainframe age. Even so, Kirschenbaum’s work generates useful research and design questions in a mainframe computing context. For instance, did the inability to edit interactively, operating on lines of text in relative isolation lead to the terse style of office memos? Would demonstrating ed, the standard line-editor for Unix systems, give contemporary computer users a sense of how line editors affect written composition on mainframes? While the current incarnation of the Mainframe Project doesn’t interrogate these questions directly, we hope that showing scholars images of these devices will spark questions related to how computer-human interaction differed in the past, and how that difference might be manifest in present day interaction.

This project takes lessons from humanities work on digital archives. Maybe no scholar has argued more passionately about the hidden costs of digital publishing than Johanna Drucker. Among her many concerns, the “cost of production and maintenance…greater with digital objects than print” because they include all of the activities required for printed material, plus “servers, licenses, files, delivery, and platform-specific or platform-agnostic design” (Drucker, 2014). The threat of format, rendering technique, and style obsolescence is real when publishing a digital work on an often unforgiving humanities and IT budget in academia. To account for these risks, the Mainframe Project uses the Wax project, an extension of the Jekyll static website generator written in Ruby, provided by the Minimal Computing work group. This choice grants the Mainframe Project the best option for durability and maintainability without a dedicated staff in the future.

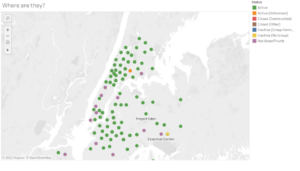

Scholars and students interested in imaginative explorations of what it might have been like to interact with and encounter mainframe interfaces in person, as well as the cultural impact it had not only in the workplace, but popular culture as well. We believe there’s a requirement for educational material for non-technical audiences in the broader public due to relative unfamiliarity with the technologies involved. Coming from CUNY, a public institution that values accessibility of education, we strive to make the collection accessible to anyone– from professional researchers, academics, to those with a more casual interest in computer history. We aim for the digital collection to be a resource for technologists, media ecologists, archivists, designers, artists, and historians alike.

Project Activities

The initial goals were to create a digital collection of archival media that were manipulated through deformance; I think we were drawn to the idea of deformance in terms of what it can do in terms of interpreting media, understanding our social social relationships and human interactions with computers by using mainframes as a point of departure. We think it is still an interesting concept to execute, however, we believe for educational purposes, it would be confusing to the segment of the audience who are non-academics. Or not even non-academics; those who are unfamiliar with what mainframes are. While presenting our final project during the dress rehearsal, fellow classmates expressed that they were not aware of what a mainframe even is. It became painfully clear that in order to address certain topics, such as gender politics in the workplace, time sharing and cloud platforms, and cultural perceptions surrounding mainframes in the 1960s, we would need to first explain how they operated. Unfortunately, this is something that we would need expert consultation on or additional time to research and express coherently to a lay audience.

Reflecting on the work plan, we spent a majority of the time planning and researching what kind of content we wanted to include in the project, which strayed off from our initial goals of mainframes themselves. Finding computer magazines aimed towards hobbyists from the 70s-80s opened up another avenue of topics to explore besides mainframes in a work-setting. Creative Computing was one of the earliest magazines covering the microcomputer revolution, which covered the spectrum of hobbyist/home/personal computing in a more accessible format than the rather technically oriented Byte magazine. The magazine was created to cover educational-related topics, and early issues include articles on the use of computers in the classroom, various programs like mad libs, and various programming challenges. It also featured editorials that explored more existential topics relating to technology creeping into functions of our everyday lives. One editorial, titled The Computer Threat to Society, talks about grocery stores switching price cards on the shelf to bar codes and how the computerized UPC system (Universal Product Code) “is indicative of the little ways that the computer is invading our lives.” It continues on with “With UPC, people are being forced to make a change that some of them don’t want to make.” It continued with topics about fraud, the influence it has on elections, the inconveniences that occur in bank statements, and even the physical harm that can come from inadvertent errors or program bugs.

Upon further research, we came upon Radical Software, an early journal started in 1970 in New York City that explored the use of video as an artistic and political medium. It was off topic to the project at hand in that there is no mention of mainframe computers itself throughout the journals, but relevant as the content itself was a call to pay attention to the way information itself is disseminated, the relationship between power and control of information, and also a call to encourage a grassroots involvement in creating an information environment exclusive of broadcast and corporate media. The journal was started by early video-art pioneer Beryl Korot, who is well known for her installation works that explore the relationship between analog technologies and video. Issues of Radical Software included contributions by nam June Paik, Douglas Davis, Paul Ryan, Frank Gillette, Charles Bensinger, Ira Schneider, Ann Tyng, R. Buckminster Fuller, Gregory Bateson, Gene Youngblood, Parry Teasdale, Ant Farm, and many others. In one publication, there was a series of poems titled Simultaneous Video Statements by Aldo Tambellini. One poem reads:

Radical Software, Vol. 1, pg 19

This piece ties mainframe computers to their involvement in warfare. While some audiences are familiar with the work done by Alan Turing to break the cryptograph code of the Enigma machine during WWII, most don’t know about the ENIAC and Harvard Mark I, two mainframe computers used to calculate the maximum blast radius for nuclear and non-nuclear bombs and bombing raids.

After that, research continued into the artistic explorations via computing beginning in the 1960s, in which computer programmers at IBM, the MIT, and other research labs experimented with computer-generated films in collaboration with artists such as Stan VanDerBeek, Kenneth Knowlton, A. Michael Noll, and John and James Whitney, among many others, highlighting the interrelationship of science and art and the collaboration between artists and engineers. The abstract films produced, most notably by artist Stan VanDerBeek in cooperation at Bell Labs, center around the new ways of seeing and new forms of sensory engagement with cinema and the world.

While exploring topics that linked art, technology, perception, and humankind, we were unaware of the technological barriers laid before us in creating a website with no experience in front-end web development. It left us with little time to tackle some of the issues regarding building a website. In hindsight, more time should have been spent on technical development, given the two-person project we were committed to operate as. It also came to light later in the semester that Wax is ideally focused on small digital collections, particularly when hosted using zero cost platforms like Github Page and similar options. Had this been realized sooner, less time could have been spent on researching topics that never ended up on the final product, as we had to lower our scope for what archival material we wanted.

Accomplishments

We created a digital collection of archival images about mainframe computers from advertising, marketing brochures and user manuals. Beyond the creation of that artifact, feedback from the CUNY digital humanities community demonstrated an interest in what most audience members felt is an understudied topic. There’s considerable interest piqued about how mainframes work, how interacting with them differed so drastically with the computers of today. The process of researching and collecting these materials reveal the potential of mainframes as a scholarly and digital humanities topic, as well as the vast subject matter one might investigate over a longer period of time.

Future plans

There are three distinct directions we want to highlight for future development of the Mainframe Project, using the digital archive we created this semester.

The most straightforward path we could pursue is extending the archive further. Due to the implementation choices made, we found over double the number of interesting images that are hosted in the archive as it exists today. As access to physical archives opens with the waning of coronavirus pandemic restrictions, we anticipate that physical brochures, magazines and other ephemera related to mainframes could be scanned for inclusion in the Mainframe Project. Moreover, video about mainframe computers could be included in the archive. Enlarging the website with archival material need not only be the only source of enhancement. The archive as it exists today is devoid of written content that could aid in the significant educational gap between classic mainframes and our popular contemporary knowledge of microcomputers. Similarly, more in depth treatment of themes and theoretical analysis could help flesh out a context through which to understand our library of visual material.

Expanding our collection would require rethinking our technical infrastructure. Moving from Github Pages to a flexible cloud host like Linode would help navigate storage limitations, and give more flexibility in terms of libraries/frameworks used to generate the site, providing better support for the expanded size of the archive and new file formats and mediums. For instance, image processing with about 250 images (the current archive size) takes about two hours. With more image files, and larger files like video, switching to a framework like Hugo would drastically decrease processing time. Moving off of low administration environments to a cloud provider, and migrating away from the Wax library would increase the development effort and maintenance required, but a more complex configuration is a reasonable tradeoff as the archive becomes more expansive.

A more traditional development path for the archival research done for the Mainframe Project would be the creation of a “thick” history of mainframes. This approach may take the form of a scholarly essay or thesis that builds up a substantive bibliography, synthesizing a historical account of mainframes used for business, explanations of how these computers were operated, a perspective on mainframes as critical infrastructure in the past and present, and theoretically focused a genetic analysis of the cultural effects of computing devices between the 1950s and 1970s. The benefits of taking this approach as a next step in the project are commensurate with the feedback we received from CUNY digital humanities community members, and would broaden the audience for academic and general non-fiction writing about mainframe computers. Computing with text and physical interfaces is foreign to even some technical audiences. But there’s also a lack of understanding of computers in culture before the personal computer revolution in the 1980s. This manifestation of the Mainframe Project could build on the cultural artifacts collected in the archive, while providing a deeper context in which to appreciate them.

The third potential path for the Mainframe Project would be an interactive web app that demonstrates how a mainframe computer works. While underdeveloped in the specifics, one could imagine virtual mainframes based on one or two machines from the Mainframe Project’s period of study, where visitors are guided with instructions on how to interact with the machine, what inputs and outputs are generated. The representations of the machines could be abstract too, with fun sounds and simplified representations to focus more on understanding the workflow rather than trying to recreate the machines in a digital format.